Science of Attraction and Beauty

“Sex and beauty are inseparable, like life and consciousness.”

David Herbert Lawrence, Sex Versus Loveliness, 1930

“The idea that beauty is unimportant or a cultural construct is the real beauty myth.”

Nancy Etcoff, Survival of the Prettiest, The Science of Beauty, 2000

Index

2. Universality of Beauty and Cultural Difference

3. Youth, Health, and Attraction

4. Science of Waist to Hip Ratio

5. Attractiveness in Human Face

6. Golden Ratio in the Human Face

8. Averageness and Exceptionality

10. Gestures and Movement—“Dynamic Attraction”

1. Introduction and Overview [index]

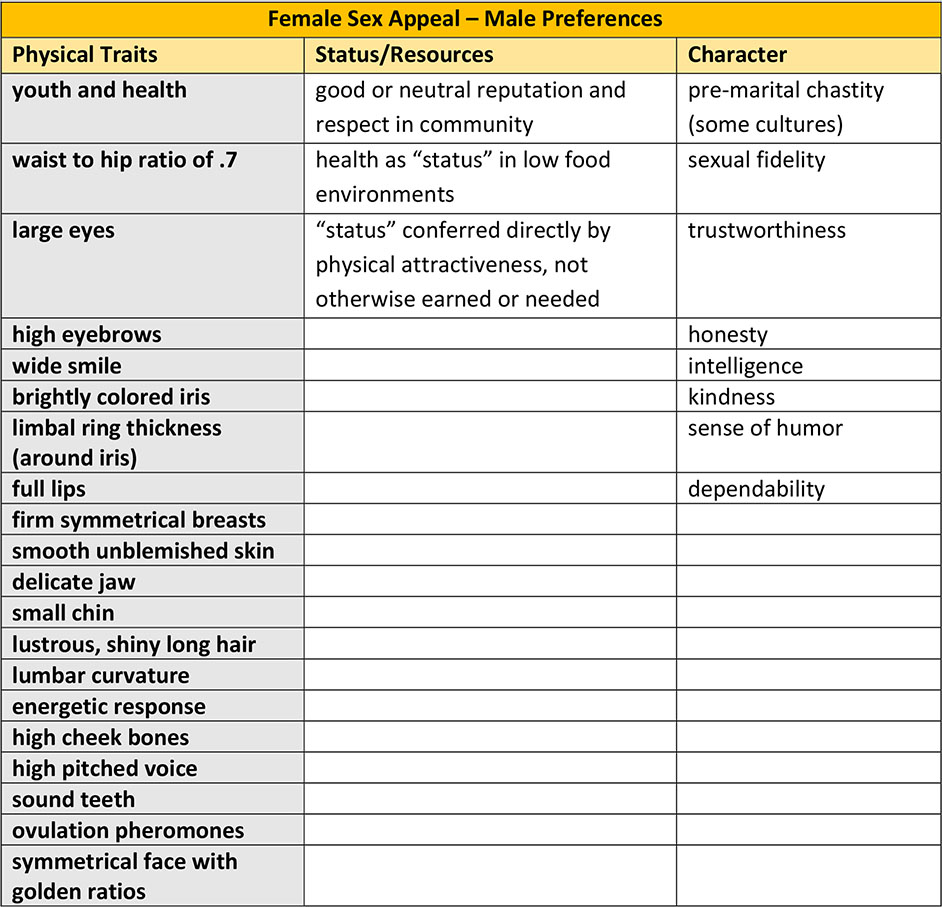

Human beings share universal, hard-wired preferences for physical traits that are pleasing to the eye — traits we find sexually attractive and aesthetically pleasing, or “beautiful.” Beauty is highly prized in prospective mates because it is a proxy for reproductive fitness and genetic strength. It is more than mere aesthetics. The science of attraction and beauty uncovers preferences fundamentally anchored in adaptive problems that men and women have to solve for mate selection. Beauty is nature’s shorthand for health, fertility, and reproductive capacity — visual cues that a woman or man has the potential to bestow good genes on future generations. For instance, facial and body symmetry signal health and size ratios of waist to hip (for women) and shoulder to waist (for men) reveal fertility and strength respectively.

What Men Find Attractive

The main adaptive problem for men is that human female ovulation is concealed. For thousands of years, human males had to detect fertility from physical cues that correlate with it. Since female fertility peaks in the mid-20s and declines to zero around age 50, cues correlated with youth and beauty evolved into a universal standard of female attractiveness. Studies show that men are drawn to markers of youth and health: bright eyes, clear skin, full lips, symmetrical faces, a sprightly gait, and a narrow waist compared to the hips. Newly discovered as a “fitness-relevant trait” is a woman’s lumbar curve. (Evolution and Human Behavior, 2016.). Female bodies that display an optimal lumbar curvature are considered more attractive by males. Evolutionary origins of lumbar curvature reflect problems faced by bipedal females during pregnancy. This curvature indicates less pressure on the spine when carrying a fetus and provided better foraging abilities in our ancient past.

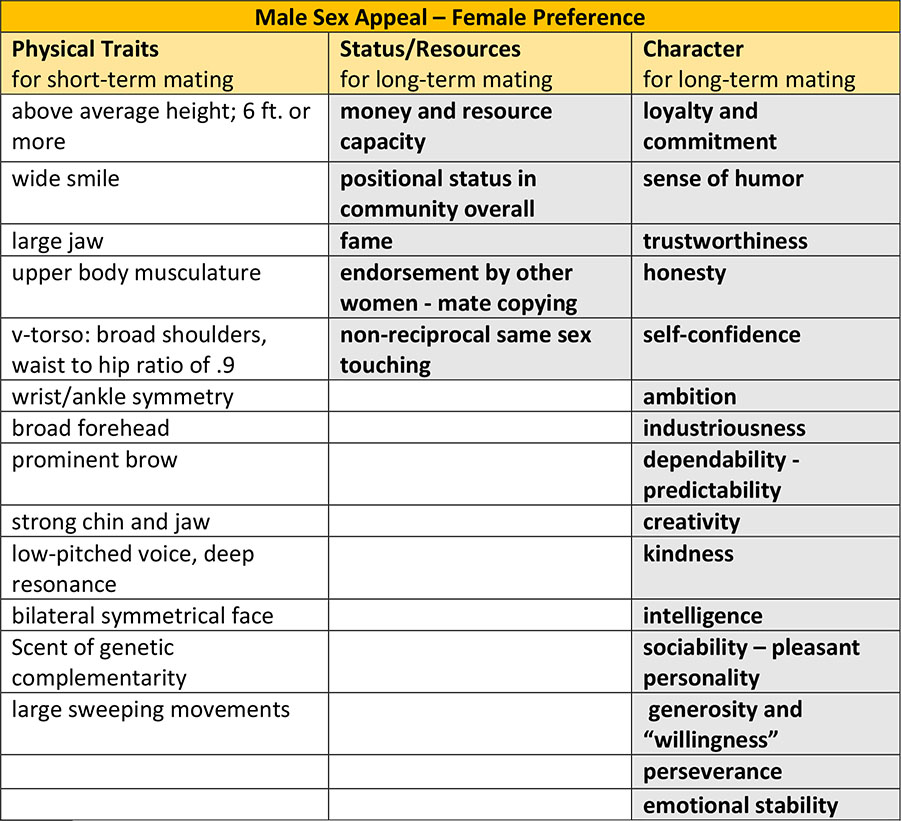

What Women Find Attractive

Women are sexually attracted to male traits related to physical size and structure, such as broad shoulders and a flat stomach, narrow hips, height, strong jawline, and a deep voice. But women also seek character traits related to a man’s position in a social/economic hierarchy — traits that solve a woman’s adaptive problem of finding protection and provision for herself and her children. These traits signify status and power within the community and capacity to provide resources — traits such as ambition, perseverance, industriousness, and intelligence. Furthermore, character traits of loyalty, emotional stability, kindness, and predictability are part of a man’s sex appeal. Humor in men is especially important in modern times because it combines intelligence, kindness and the capacity to generate a safe and positive mood.

A man’s sex appeal is found in three domains: physical, status/resources, and character. In contrast, the initial sex appeal of a woman has almost nothing to do with her status or capacity for provision of resources, and only marginally about her character traits. These gender differences in attraction are significant. A man’s perception of attraction and beauty is predominantly visual — what he sees in a woman that communicates youth (nubility) and fertility. Male visual orientation is significantly stronger than female visual orientation for sexual attraction and beauty. (See blog: Is Your Sexual Foot on the Accelerator or Brake?)

However, women are significantly more contextual in sexual response. Male behaviors that communicate status or character directly interact with her visual perception of attraction. For instance, a man’s appearance in clothing can affect her assessment of his status and resource capacity and even influence, studies show, her impression of his physical attributes.

Both men and women use hearing, sound and smell to assess attraction, but studies indicate a woman’s use of smell is more acute and more important in creating desire. The female voice (sound) is important to men but the male voice is more important to the female experience of attraction. Women find more “deal breakers” in how a man smells, sounds, or tastes than do men find deal-breakers in these realms.

In addition to physical characteristics that are sexually attractive, there are other human system dynamics at work: both sexes seek similar traits of social status, intelligence, and levels of perceived “mate value” (assortative mating). Both sexes are attracted to people who attract others (mate copying), and attracted to people who are most attractive in comparison to those near-by (contrast affect).

Desirable male physical traits – height and torso

Women prefer men who are six feet or taller. They prefer tall men as marriage partners and place a greater emphasis on height in short-term partners. “Big men” (a term coined by author and anthropologist Helen Fisher) in hunter-gatherer societies — high-status men who commanded respect, and tall men in Western cultures, tend to have more socioeconomic status than short men. Height is considered an “honest signal” of a man’s ability to protect. Tall men tend to be healthier, have more resources and many adaptive benefits.

Studies reveal that women desire muscular, athletic men for long-term mating and sexual liaisons (David Buss, Evolution of Desire). Women show a preference for a particular body morphology – a V-shaped torso with broad shoulders relative to hips. Hip to shoulder ratio signaled good hunting and protection in the ancestral environment. Men exhibiting a high shoulder to hip ratio begin having sex at an early age (16 or younger) and they report having more sex partners than slim-shouldered peers (Buss and Meston, Why Women Have Sex). They have more affairs while in relationship and report more instances of being chosen by already mated women for sexual affairs on the side. Potential rivals with a high shoulder to hip ratio trigger more jealousy in men.

2. Universality of Beauty and Cultural Difference [index]

There is nothing arbitrary about the image of ideal female beauty; it has been precisely and carefully calculated by millions of years of evolution by sexual selection. Visual beauty standards do vary between cultures and eras, but signs of youth, fertility and good health, such as long lustrous hair, or smooth, scar-free skin, and a low waist-to-hip ratio, are always in demand because they are associated with reproductive fitness.

The most culturally variable standard of beauty is perhaps the preference for a slim vs. plump body build. The Western ideal considers a slim and slender body mass as optimal, while many historic cultures consider a plump body mass appealing. This variation is linked with the social status that body build conveys, says evolutionary psychologist David Buss. In countries where food is scarce, such as among Bushman of Australia, plumpness signals greater health and adequate nutrition during development. In societies where disease and starvation are prevalent, a heavier woman advertises health and access to resources, while a thin woman signals disease. In cultures where food is relatively abundant, such as the United States and in Western Europe, the relationship between plumpness and status is reversed.

Mostly there is cross-cultural agreement at the foundation of what attracts, of what is considered physically beautiful. This “agreement” inside the bell curve drives evolution. The outliers of individual difference will always be there, but it is most correct to say that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and most beholders agree to what that is.

3. Youth, Health, and Attraction [index]

Youth is a proxy for health and health is universally attractive to both sexes. However, youth is especially attractive to men and a powerful component of their perception of beauty.

Youth (nubility) is a critical cue since a women’s reproductive value declines steadily with age after twenty. Men’s preoccupation with a woman’s youth is not limited to Western cultures. Without exception, in every one of the 37 societies in which David Buss studied, men preferred wives who were younger than themselves, on average by 2.5 years. Statistics derived from personal advertisements in newspapers reveal that a man’s age has a strong effect on his preferences. As men get older, they prefer mates that are increasingly younger than they are. Men in their thirties prefer women who are roughly five years younger, whereas men in their fifties prefer women who are 10 to 20 years younger.

According to a 2014 study in Finland, men of all ages fantasize about women in their 20s. Researchers surveyed 12,656 men and women, aged 18 to 49, in an attempt to study age preferences in sexual partners. Women tended to be interested in men who were similar in age or slightly older. Men were mostly interested in one single age group: women in their mid-twenties. This held true even for men in their later teens or early twenties. Researchers argued that male and female age preferences have their roots in evolutionary biology. Women go for older men due to the resources they can offer, including their ability to help with offspring. Researchers believe men’s sexual preferences, their attraction and assessment of beauty, are shaped with offspring in mind. Highest fertility is estimated to occur in a woman’s mid-twenties, with a decline after age thirty-five.

A man’s preference for youth stays pretty much the same as the women in his circle get older. This is counter-balanced to some degree by the influence of assortative mating in the mating economy. While men’s instinctual preferences are stable, his opportunities and choices are not. But in the words of David Buss, “railing against men for the importance they place on beauty, youth and fidelity, is like railing against meat eaters because they prefer animal protein. Telling men not to become aroused by signs of youth and health is like telling them not to experience sugar as sweet” (Evolution of Desire, p. 71).

4. The Science of Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) [index]

Men apparently do not have an evolved preference for a particular amount of body fat. Rather, there is a preference for how that fat is distributed. Much of a woman’s mate value can be detected from visual cues. Anything that interferes with fertility, such as obesity, malnutrition, pregnancy, or menopause, changes a woman’s shape. There is no better visual cue than the relative contours of her waist and hips. As discovered by evolutionary psychologist, Devendra Singh, if you divide the circumference of the female waist by the circumference of her hips, she will be perceived as more sexually attractive if that ratio is close to .7.

Puberty, Hormones, and the WHR

The reason for this is related to puberty and hormones. Men have an innate preference for female bodies with narrow waists and full hips because they signal high fertility, i.e. high estrogen and low testosterone. Waist to hip ratios do not differ in pre-pubescent boys and girls; it is about .9 for both. At puberty, the ratio begins to shift downward for females, but not for males. As women age, their ratio begins to creep up again. Before puberty and after menopause, females have essentially the same waistlines as males. But during puberty, a typical girl gains nearly thirty pounds of so-called reproductive fat around the waist and hips.

Those pounds contain roughly 80,000 calories needed to sustain a pregnancy; the curves they create provide a gauge of reproductive potential.

Healthy, fertile women typically have waist-to-hip ratios of .6 to .8; their waist is 60 to 80 percent the size of their hips, whatever their actual weight. Researchers in the Netherlands (1993) discovered that even a slight increase in waist size can signal reproductive problems. A study of 500 women who came for artificial insemination proved the link of WHR to fertility. Among women attempting in vitro fertilization, the odds of conceiving declined by 30 percent with every 10 percent increase in WHR. A woman with a WHR of .9 was nearly one third less likely to get pregnant than one with a WHR of .8, regardless of her age or weight.

Men in 18 Cultures Prefer WHR of .7

Psychologist Devendra Singh tested men’s perceptions of body shape in eighteen cultures. He showed people line drawings of women at three different weights (underweight, average, and overweight) and three different WHRs (.7, .8, .9) and asked them to choose which figure is the most attractive. Overwhelmingly, men in his studies chose the average-weight woman with the .7 WHR as the most attractive.

Icons of Beauty and WHR

If one looks at the icons of beauty, Singh’s findings about body shape become apparent. Audrey Hepburn and Marilyn Monroe represented two very different images of beauty to filmgoers in the 1950s. Yet, 36-24-34 Marilyn and the 31.5-22-31 Audrey both had versions of the hourglass shape and a WHR of .70. The supermodel Elle MacPherson, known as “The Body,” not only has 44-inch legs but measurements of 36-24-35, a curvy .69.

While our ideals of size might change (Twiggy vs. Rubenesque), our taste in shapes is amazingly stable. Singh also compiled measurements of Playboy centerfolds and Miss America winners from 1923 to 1990. Their bodies got measurably leaner over the decades, yet their waist to hip ratios stayed within the narrow range of .68 to .72 (even Twiggy had a WHR of .73).

In the US, obesity has such a great influence on people’s perceptions of attractiveness that neither breast size nor WHR can override it. While men prefer the hourglass shape, it won’t lead them to prefer an obese woman over a thin or average-weight woman with a more tubular body. In Singh’s studies, the heaviest figures were judged to be 8-10 years older than the slimmer ones (even though the faces were identical).

5. Attractiveness in Human Face [index]

The facial features humans are attracted to are precisely the ones that diverge in males and females during puberty, as a flood of sex hormones wash us into adulthood. These hormonal effects would have been a good clue to mate value in the hunter-gatherer world where preferences evolved.

The Female Face

The tiny jaw that men favor in a woman is essentially a monument to estrogen, and obliquely to fertility – signaling the increased odds that she could get pregnant.

Social psychologist Michael Cunningham at the University of Louisville found dimensions and proportions of the ideal female face to be large eyes, small chin and nose, high cheekbones and narrow cheeks. These traits are signs that a woman has reached puberty. High eyebrows, dilated pupils and wide smile signal excitement and sociability.

Cunningham also found that men are looking for lips that have “fullness, redness and warmth.” Likewise, scientists from Manchester University found that after meeting a new woman, men spend half of their interaction looking at their lips. They hypothesized (as have other researchers) that red lips mimic the widening of blood vessels that occurs with sexual arousal.

The Male Face

The heavy lower face that women favor in men is a visible record of the surge in androgens (testosterone and other male sex hormones) that turn small boys into 200-pound athletic men. Ovulating heterosexual women and gay men prefer faces with masculine traits associated with testosterone such as heavy brows, wide jaws, and broad cheekbones.

Only men with above-average health in adolescence can “afford” to produce high levels of testosterone that masculinizes the face. A man’s masculine-looking face signals health, his ability to succeed in competing against other men, and his ability to protect.

Women find above-average masculine faces to be sexiest and most attractive for a casual sexual encounter, but find less masculine faces more attractive for a long-term relationship.

It has been reported that square-jawed men start having sex earlier than their peers and attain higher ranks in the military.

Baby Face Phenomenon

Large eyes, thick lips, relatively short nose, and a large curved forehead are considered baby face traits. Many studies indicate that this “baby face phenomenon,” or the tendency to find infant-like facial features attractive, occurs not only because these features suggest youth, but also because they elicit the same warm feelings as our typical response to babies, both human and animal.

Speaking of babies, psychologist Judith Langlois and colleagues studied infants and their social responses to faces and found that infants looked longer at more attractive faces. This suggests that standards of beauty emerge quite early in life and challenges the common view that attractiveness is learned through gradual exposure to cultural standards.

“The Eyes Have It”

While large, wide-set eyes are a predominant feature of female beauty in particular, both men and women like a brightly colored iris, free of cloudiness and redness. Men are more attracted to women with a clear sclera, according to The Harvard Brain. Dull or dry eyes are associated with aging. We also perceive people to be more attractive when their pupils dilate — dilation is correlated with positive emotions.

The limbal ring is the dark circle toward the edge of the iris that signals youth or health in both men and women. It tends to fade as we age, beginning sometime in the mid-twenties.The thickness of the limbal ring may contribute to facial attractiveness. Limbal rings are more pronounced in lighter colored eyes than in darker ones.

6. Golden Ratio in the Face [index]

The golden ratio or golden rectangle is one of the most satisfying of all geometric forms. It is a mathematical relationship (a/b = (a+b)/a = 1.618…) that appears in all of nature and science: plants, animal bodies, painting, architecture, sculpture and even music. It has been called the “divine proportion.”

The golden ratio occurs repeatedly in the dimensions of the human face and produces our perception of balance and physical beauty. The human head forms a golden rectangle with the eyes at the midpoint. The mouth and nose are each placed at golden sections of the distance between the eyes and the bottom of the chin. And this is just the beginning of the geometrical beauty that appears in the human face. The golden ratio can be found in more than twenty facial calculations. Human facial beauty is based on divine proportion. Beautiful women throughout history, from Queen Nefertiti to Marilyn Monroe, display the golden ratio in the face.

A relatively new science, called neuro-aesthetics, addresses human visual appreciation for beauty from a mechanistic perspective and interfaces with expressions of the golden ratio. Humans have a well-developed visual aesthetic sense that applies to numerous domains such as the fine arts, natural sciences, and of course sexual beauty. Visual neuro-aesthetics asks the brain why it likes what it sees. (Michael Ryan, Taste for the Beautiful, The Evolution of Attraction)

7. Bilateral Symmetry [index]

Humans and most other animals are bilaterally symmetric. The left and right sides of the body are basically the same, including the face in humans. Small deviations from this symmetry are called “fluctuating asymmetry” (FAs). Behavioral ecologist Randy Thornhill and other researchers have discovered a preference for symmetry (low FAs) and its influence on human perception of sexual beauty. A bilaterally symmetrical face is a cue to genetic quality and developmental stability. When humans or animals are stressed during development, their bodies and faces are more asymmetric. In animals, symmetry is a sign of parasite resistance, survival, and fecundity. In a review of 62 studies conducted with 41 species, zoologist Anders Moller and Thornhill found that low FAs were associated with mating success or sexual attractiveness in 78% of species, including the human species.

Men with symmetrical bodies tend to have other attractive features such as symmetrical faces and bodies that are more muscular, taller, and heavier than those of men with less symmetrical bodies. Thornhill found men with symmetrical bodies were more athletic and more dominant in personality than their peers. He also found that symmetrical human males started having sex three to four years earlier than asymmetrical males, have sex earlier in the courtship, and have two to three times as many partners.

Legions of researchers have shown that we are often attracted to more symmetrical faces. In 1995, Steven Gangestad and Thornhill survey 86 couples and found that women with highly symmetrical partners were more than twice as likely to climax during intercourse than those with low-symmetry partners. (They also found that extremely symmetrical men were less attentive to their partners and more likely to cheat on them.) Fluctuating asymmetry turned out to be a better predictor of female orgasm than the couple’s feeling of love, the investment of either party in the relationship, the male’s potential earnings, or the level of sexual experience or frequency of lovemaking of the couple. When women have extramarital affairs, they tend to choose symmetrical men as partners.

Symmetrical women were favored too. They have more sexual partners than less symmetrical females, and may be more fertile. One study found that women with large symmetrical breasts were more fertile than women with less evenly matched breasts. Interestingly, women’s symmetry changes across the menstrual cycle. They are more symmetrical (and presumably more attractive to their partners) on the day of ovulation.

8. Averageness and Exceptionality [index]

Humans love “average” faces (koinophilia). The more “average” you are, or closer to the mean of all people, the more attractive you are perceived to be. From an evolutionary perspective, a preference for extreme normality makes sense, says researcher Judith Langlois: “individuals with average population characteristics should be less likely to carry harmful genetic mutations.”

Langlois had subjects rate composite faces (made of 16 or more images morphed together) against individual faces. The composite faces were rated more attractive. According to Langlois, “if you take a female composite face made of 32 faces and overlay it on the face of an extremely attractive female model, the two images line up almost perfectly. The model’s facial configuration is very similar to the composites’ facial configuration.” And this was also true for the men’s composite faces. Langlois also found that infants as young as one year old responded to this kind of “averaged” attractiveness in adult faces.”

Langlois further explained this phenomenon by finding that people prefer prototypes because they are so easy to categorize. “Beautiful faces are easy on the eyes and also easy on the brain — they are easier to process,” she said. Attractive faces require less effort to perceive and categorize than unattractive ones. “We prefer things that require less processing effort and that seem more familiar.” In a related study, Langlois and her colleagues found physiological evidence that “ugly” faces take more cognitive resources to perceive than pretty ones, even among babies. This phenomenon may lay the foundation for later social preferences for attractive people.

Yet, paradoxically, the faces we find MOST attractive are not average! Victor Johnson at New Mexico State University found the “ideal” female had a higher forehead than average, fuller lips, shorter jaw, and smaller chin and nose. The most exquisite people apparently are slightly away from average. “Average faces are attractive, but they are not usually the most beautiful. Maybe it’s the exaggerations of certain features the creates celestial features,” Johnson wrote.

9. Sound (Voice) and Smell [index]

Heterosexual women respond to the male odor and heterosexual men respond to the female scent in their hypothalamus, a part of the brain involved in sexual arousal, rather than in the olfactory center of the brain, where all other odors are processed. The nose’s contribution (smell) to romance is more than noticing perfume or cologne. It’s able to pick up natural chemical signals known as pheromones. Michael Ryan in A Taste for the Beautiful explains that pheromones and odors are not the same, even though we tend to use them interchangeably. A pheromone is an odor-signal, evolved to inform. Pheromones not only convey important physical or genetic information about their source but are able to activate a physiological or behavioral response in the recipient. In his chapter entitled “The Aroma of Adulation,” Ryan argues that olfactory cues are often the best way to make a critical decision about who is a willing and able mating partner. “The link between genes and odors is probably shorter and more direct than the same links in other signals” (p. 111).

The Smell of Female Beauty (Ovulation)

In one study (called the “stinky tee shirt experiment”), a group of women at different points in their ovulation cycles wore the same T-shirts for three nights. After male volunteers were randomly assigned to smell either one of the worn shirts or a new unworn one, saliva samples showed an increase in testosterone in those men who had smelled a shirt worn by an ovulating woman. Evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller, in The Mating Mind, reported that men in strip clubs tipped more for a lap dance when the dancer was ovulating. Miller argued that the dancer’s odors caused the enhanced generosity of their patrons.

The Smell of an Attractive Man; It is in his Genes

A first priority in mate choice is getting a partner with complementary genes. The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a set of genes that function in human immune response. The best choice of mate, and co-parent, has MHC genes that are different from the chooser; this yields offspring better armed to fight disease than either parent.

A woman’s nose is particularly attuned to MHC molecules. In this case, opposites attract. When a study asked women to smell T-shirts that had been worn by different men, they preferred the odors of those whose MHC molecules differed from theirs. This makes sense. Genes that result in a greater variety of immunities may give offspring a major survival advantage.

Women can also detect the scent signature for symmetry. More symmetry means a lower mutation load. Odors of symmetrical men are more attractive; asymmetrical odors are repulsive. Women’s olfactory acuity reaches its peak around the time of ovulation.

The Sound of Female Beauty

Men prefer females with high-pitched, breathy voices, and wide formant spacing, correlated with smaller body size. A higher-pitched female voice is judged to be younger and hence, more attractive.

The Sound of an Attractive Man

Women prefer a low-pitched male voice with deep resonance (narrow formant spacing). This type of voice suggests a larger body size and is linked to symmetry, facial attractiveness, digit ratios, and other features optimized by testosterone.

Evolutionary anthropologist David Puts obtained voice recordings of men attempting to persuade a woman to go out on a date. Women rated voices for a short-term encounter and for a long-term committed relationship. They preferred a deep voice for both but more so for short-term encounters. Women in ovulation phase showed the strongest attraction to the deep voices.

Psychologist Susan Hughes found that men with sexy voices have a higher shoulder to hip ratio — the V-shaped torso. Another study found American men with lower-pitched voices had a larger number of sex partners than men with higher-pitched voices.

A second study of the Hadza, a population of hunter-gatherers living in Tanzania, found that men with lower-pitched voices had a greater number of children, possibility as a consequence of having greater sexual access to fertile women.

A testimony to the strength of this effect was recently demonstrated on the NPR radio show “Wait-Wait… Don’t Tell Me.” Radio host, Bill Curtis, with a signature deep voice, spoke to a call-in guy with a great voice: “maybe we should do a tone-off,” Curtis joked. At the prospect of that, the listening female contestant enthusiastically proclaimed, “I just might ovulate!” Active listening indeed.

10. Gestures and Movement – “Dynamic Attraction” [index]

Men and women (especially) are attracted to how a person moves and gestures — to emotional expressiveness, what researchers call “dynamic attraction.” Psychologists Paul Eastwick and Eli Finkel looked at people’s choices on online dating apps and found that individuals were twice as likely to choose prospective dates whose pictures displayed “postural expansiveness-expanding the body is physical space.” Their research revealed that women find certain body movements to be more attractive than others. Men with larger and more sweeping movements were rated as more erotic in a study of pixelated images of them dancing.

David Buss and Cindy Meston (Why Women Have Sex) reported that men and women have distinctive walks. “Men’s upper bodies sway laterally more than a women’s. Women, in contrast, have a hip rotation in opposite phase to their vertical leg movement, creating that classic hip swivel” (p. 18). Studies by psychologist Meghan Provost found that women preferred men who had an above-average masculine walk.

Other patterns of men’s movement provide women with valuable mating information. Evolutionary psychologist Karl Grammer and colleagues found five classes of men’s movements linked with successful contact with women: 1) more frequent short, direct glances at women; 2) more space maximization movements; 3) more location changes; 4) more non-reciprocal touches and 5) a smaller number of closed-body movements.

Women are drawn to men who signal with eye contact, open body posture, and social status through space maximization, a masculine manner of walking and non-reciprocal intra-sexual touch. When a man touches another man’s back, it is seen as a signal of dominance. Women see touchers as having more status.

11. Assortative Mating – Like Attracts Like [index]

We generally seek partners who resemble us in terms of appearance, height, education, IQ, and socioeconomic status. This is called assortative mating. For instance, geneticists at University of Queensland found a strong correlation in the genetic markers for height between partners in more than 24,000 married couples. (Women, in particular, are less likely to partner with a man shorter than them.)

The tendency to seek partners who have relatively similar “mate value” (in “our league” or a bit above) makes sense in a mating economy that rewards effort where mating success is more likely. Going for someone substantially more desirable is often a losing proposition for both men and women. If you lure a more desirable mate, there are costs such as the need to be ever vigilant of mate poaching.

However, there is a parallel cross-current to the practicality of assortative mating that is part of the female mating strategy. “Hypergamy” is a term social scientists use to refer to the phenomenon of women prioritizing wealth or social status in mate selection. This is well documented in mate selection studies within the field of evolutionary psychology. It has been observed by Jordan Peterson (Canadian psychology professor and iconoclastic YouTuber) that “women tend to mate across and up dominance hierarchies and men mate across and down.” (Mating across is assortative mating.) Women will “sort” for similarity but with an eye for an “upgrade,” according to this view. For instance, in a Columbia University speed dating experiment, men’s interest in a woman’s intelligence peaked at a rating of seven. A man’s interest went down if the woman scored a perfect ten on intelligence. For women, however, the smarter the man the better. (Why Women Have Sex.)

12. Character, Status, and Personality [index]

Cross-cultural research by evolutionary psychologist David Buss (Evolution of Desire) revealed that men and women world-wide want mates who are intelligent, kind, understanding, dependable, trustworthy, honest and with a sense of humor. But the emphasis on these traits for female sex appeal is decidedly less strong than what is required for male sex appeal. The science about character, status, and personality for mate selection is primarily a story about what women want from men in order to mate with them.

The Character Women Want from Men

Character in a mate is a crucial part of a woman’s long-term mating strategy. Many character traits are desired that correlate to and synergize an ongoing capacity and willingness to provide safety and resources to a woman and her children. Compared to other primates, humans need a high level of male parental investment (MPI) due to the vulnerability of offspring.

Character Traits Signaling Capacity

In 1989, Buss published his pioneering study of mate preferences in 37 cultures around the world. He found that in every culture, females placed more emphasis than males on a potential mate’s financial prospects. In addition, he found that women wanted the character traits of ambition and industriousness, traits associated with future capacity and positive mate value trajectory.

Creativity is another trait cluster associated with increased mental capacity and is a signal of genetic fitness. Creativity operates in sexual selection because there is ample genetic variability underlying it. Not everybody is creative. Musical talent, story-telling ability, artistic expression, humor, and poetic dexterity of language are desirable premiums in a partner. Psychologist Glenn Geher: “Every marker of creativity seems to play into mating — being attracted to someone creative means that person’s creativity could help you, and those genes could pass on to your offspring.” (Psychology Today, July-August 2017). Geher explains in Mating Intelligence Unleashed how creativity is a powerful mental courtship display. He cites (p.27) the work of Daniel Nettle and Helen Clegg who found that professional male artists and poets had about twice as many sexual partners as other people. The effect was not true for female artists.

Attraction to Status and Power

“Men often forgo their health, their safety, (and) their family life in order to get rank, because unconsciously they know that rank wins women.” (Helen Fisher, Anatomy of Love)

How well a man can provide has always been associated with his social status. What mattered in ancestral environments was not actual wealth (because everyone was equally “poor”), but a man’s placement in the dominance hierarchy (as with our chimpanzee ancestors.) Status among hunter-gatherers translated into power and influence over divvying up resources. Men took turns getting food from their kills, and the turns went in order of status – the highest-ranking man got the best food to take home to his woman. Today, money is the take-home; men wish to “make a killing” financially.

Status in modern times is achieved by attaining a relative position in a social hierarchy — a chosen profession, a rung on a career ladder, political and organizational leadership, or dominant influence in any social group. As stated above, attraction is enhanced with physical movements that communicate status. For instance, non-reciprocal same-sex touching signals male dominance and sociability and sends subliminal messages that resonate inside a woman’s brain.

Status sometimes comes with notoriety and fame. Fame generally brings abundant resources, a direct source of attraction. Fame is often linked to additional self-confidence and attraction by other women, producing a phenomenon called mate copying.

Self-confidence is Golden

Self-confidence is the gold standard of character traits that attract women. Self-confidence signals resources and is a proxy for status in a social hierarchy. Indeed, men scoring high in self-confidence earn significantly more than men with low self-confidence. Self-confidence is a signal of self-perceived high mate value.

Character Traits Signaling Willingness

Underscoring Buss’ research, Robin Wright (The Moral Animal) cites a woman’s need to assess a man’s willingness to invest, saying “a female in a high MPI species may seek signs of generosity, trustworthiness, and especially enduring commitment to her in particular.”

Enduring commitment had survival implications for ancestral women and her children. It is a hard-wired preference in the female long-term mating strategy. The likelihood that a man will “stay” to protect and provide is more assured if there is a set of character traits called “the stability suite” (Geher and Kaufman, Mating Intelligence Unleashed, p.57). The stability suite includes emotional stability, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Women prefer these character traits in a long-term mate.

It Pays to Be Funny

Studies from the Buss Evolutionary Psychology Lab reveal that displaying a good sense of humor is the single most effective tactic men can use to attract women. Women are attracted to men who produce humor because laughing elicits a positive mood. Humor is very agreeable and is linked to the traits of generosity and willingness.

Paradox of Power and “Stability Suite”

A women’s dual, long-term mating strategy seeks to find the most dominant male who will stay with her and be agreeable to her and her children. This “trade-off” problem is described and documented elsewhere by this author. (See Double Binds Imposed on Men.) Power is sexually attractive in an absolute sense. Often this power is enhanced by a matrix of “dark triad” personality traits: narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Studies have shown that men with dark triad traits have more sex partners. This “bad-boy” is alluring because he doesn’t care about rules; he seems more fearless, in control, and living a “bigger” life. Long-term security is generally a mate preference deal-breaker for women, but this kind of adventure and risk is undeniably sexy in the right context. Such men are more “suitable” for short-term liaisons. These personality traits are sometimes “combustible,” creating a volatile yet charming attraction elixir. The attraction of women to dark triad traits unfortunately provides fertile soil for the growth of double-bind messaging to men who wish to demonstrate character traits of “willingness.”

The Character Women Want from Men, Bottom-line

One summation of the character that women want in a man is provided by Glenn Geher and Scott Barry Kaufman in Mating Intelligence Unleashed (p. 182): “The ideal man (for a date or romantic partner) is one who is assertive, confident, easygoing and sensitive, without being aggressive, demanding, dominant, quiet, shy or submissive. Again, this fits the profile of the prestigious man.”

The Character Men (Don’t) Want from Women

For men, character is less important. This is totally predicted by the evolutionary logic of mate selection. David Buss found that out of 67 potentially desirable traits in a partner for a casual affair, men had lower standards than women on 41 of them. Buss writes that men “require lower levels of assets such as charm, athleticism, education, generosity, honesty, kindness, independence, intelligence, loyalty, sense of humor, sociability, wealth, responsibility, spontaneity, and emotional stability.” (Evolution of Desire)

When asked about undesirable traits, men had fewer problems with “mental abuse, violence, bisexuality, dislike of others, promiscuity, selfishness, lack of humor, and lack of sensuality.” Buss found that men rated only four characteristics as less desirable than did women: low sex drive, physical unattractiveness, need for commitment, and hairiness.

In addition, ancestral men sought pre-marital chastity ad post-marital sexual loyalty. Before the use of modern contraceptives, chastity provided the cue to future certainty of paternity. In the 1930s, men viewed chastity as indispensable; but since that time, chastity has declined significantly as a preference for men. Despite cultural variations, sexual fidelity still remains a strong preference for men’s long-term mate.

In summary, it is clear that character, status and personality are critical elements in the science of attraction. There are many context-specific variables related to these components of mate choice operating in the minds of modern-day men and women. However, “in spite of how much the environment has changed, our evolved mindset is based on ancestral conditions” Geher & Kaufman, Mating Intelligence Unleashed).

13. Mate Copying [index]

In the movie Legally Blonde, a snooty young woman blows off a request for a date by an awkward young man saying “Women like me don’t date losers like you.” The charming, beautiful and mischievous Elle Woods, played by Reese Witherspoon, happens to hear the conversation and feels bad for the guy. So, she approaches him and asks him, tearfully, how he could have broken her heart like that! She then darts off with a fake broken heart. After Elle leaves, Miss Snooty, who has been eavesdropping, goes back to the guy asks, “So, when did you want to go out?”

A person becomes more attractive when others find him or her attractive. Women find men sexier when they are surrounded by other women vs. when they are alone or with other men. The more attractive the woman is, the more attractive is the man as perceived by other women. Women use endorsement by other women as a basis for their own mate choice. This phenomenon is known as mate-copying by evolutionary psychologists. Social psychologists say this is a form of “social proofing.”

Biologists find mate copying in many species. From fish to mammals, females prefer males who have been pre-approved by other females. Buss found in his lab that the higher the quality of females who have chosen a given male, the stronger is the mate copying effect. Buss found an opposite reaction for men; women surrounded by other men were perceived as less desirable.

Mate copying is one reason fame is so sexy, independent of (if you can separate) status and resources. Fame and adulation have a desirability enhancement effect for men.

Mate copying in humans is also explained by the “sexy son hypothesis.” By mating with men who can attract women, it is assumed that their sons will also have those traits (genes) and be attractive to females and thus deliver those genes into future descendants.

14. Contrast Effect [index]

The contrast effect is a principle of perception whereby the differences between two things are exaggerated depending on the order in which those things are presented. Men are more susceptible than women to the contrast effect as it relates to physical beauty.

Psychologists Sara Gutierres and Douglas Kenrick demonstrated how the contrast effect operates in the sphere of person-to-person attraction. In a series of studies, they found that judgments of attractiveness depend on the current environment of potential mates. A woman of average attractiveness seems a lot less attractive than she actually is if a male viewer has first seen a highly attractive woman. In one study, men shown pictures of women’s beautiful bodies in erotica rated a previously attractive nude as less exciting. The contrast principle also works in reverse. A woman of average attractiveness will seem more attractive than she is if she enters a room of unattractive women.

Gutierres and Kenrick also found that the contrast effect influences views of ourselves and our own mates. Once introduced to what researchers called the “Vogue factor” – a measure of the influence of beauty, they found people become dissatisfied with their sexual partners. Some men even claimed to be less in love with their wives. Research shows the contrast effect has particularly afflicted college professors who see beautiful, young women in their classes day after day.

15. Beauty and Sexual Response [index]

Beauty has its sexual privileges. Nancy Etcoff (Survival of the Prettiest) summarizes research findings from evolutionary psychology that good-looking men and women are more sexually experienced and engage in a greater variety of sexual activities. Both attractive men and women begin to have sex earlier. Studies by psychologists Randy Thornhill and Steven Gangestad suggest that attractive men are more likely to have women orgasm.

Etcoff opines that “good looking people don’t have any monopoly on great sexual technique but they do have more opportunities, and without much effort, they have already engaged the fantasies of their partners.”

Ectoff reports that men are more likely to make sexual inferences about women based on their appearance. “Men are much more likely to believe that attractive women are sexually permissive, high in sex drive, and sexually confident.” This phenomenon is closely tied to a man’s natural “over-perception bias” – an elevated belief in the possibility of a woman’s interest in him which prevents a costly evolutionary “error” of not taking advantage of a mating opportunity. Male inferences in this realm are a testimony to the powerful visual phenomenology of female beauty on the male brain. A man unconsciously projects: how could someone who evokes such sexual energy in me, not be someone sexually available and interested? (An analogy might be a cigarette smoker who cannot imagine how something that pleasurable to them could, second-hand, be so toxic others.)

16. Physical Attractiveness in the Digital World [index]

The advent of social media and dating apps has increased the premium placed on the physical beauty of the face, overall physical traits of attractiveness, and split-second cognition of the human brain to determine overall desirability. This increased emphasis on visual cues has perhaps changed the calculation of women more than men. Men have always relied heavily on immediate visual cues to determine attraction. Now women may rely more on the visual, as an entire generation re-wires the brain with the addictive impulse to swipe left or right.

17. Benefits of Beauty [index]

Researchers have found that good looking students get higher grades from their teachers than students with an ordinary appearance. Studies of mock criminal trials have shown that physically attractive defendants are less likely to be convicted, and if convicted, receive lighter sentences than less attractive defendants. Beautiful people receive more acts of helping and altruism than the average person. Attractive waitresses receive higher tips from men than their average-looking peers. Beautiful women receive more allowances from men for character deficits and mean behavior than do average looking or unattractive women. Products represented by beautiful people sell better and have a better reputation, as every advertising and marketing professional knows. Some studies have shown that attractive people are more likely to be hired in a recession.

Research also reveals that people assume beautiful strangers have a host of other attractive attributes, such as intelligence, competence and kindness. Many believe this association is born by cultural influences.

Research by Judith Langlois suggests the association of beauty with goodness may be acquired at a very early age through innate information-processing mechanisms. For instance, a 1987 study published in Developmental Psychology (Vol. 23) showed that infants as young as two months prefer to look at pretty faces, an age when they probably have not had the chance to pick up many cultural cues about beauty. (See “baby face phenomenon” above.) Attractive faces may gain some of their positive associations because they require less effort to perceive and categorize than unattractive ones. Taken together, Langlois’ research suggests the well-established bias toward attractive people may be an unavoidable consequence of the mechanics of human cognition.

Beauty Pays

Female sexuality is a fungible asset – it can be readily exchanged for other goods and services and can provide direct economic benefit. The most beautiful people have the most power to trade on their physical looks, as explained by the “father of pulchronomics” (the economics of beauty), Daniel Hamermesh in his book, Beauty Pays. “The economic approach treats beauty as scarce and tradable. We trade beauty for additional income that enables us to raise our living standards and for non-monetary characteristics of work and interpersonal relations,” says Hamermesh. “Researchers in other disciplines, particularly social psychology, have generated massive amounts of research on beauty, particularly in marriage markets.”

Hamermesh goes on: “If men agree on feminine beauty, just as in labor markets, those women viewed as beautiful will command a higher price, either explicitly or in the form of husbands who can provide them with more resources. They will obtain more and better food, an easier lifestyle, more freedom to do what they want, and other benefits.” Evidence supports the correlation between physical beauty and the value of “courtship gifts,” especially the size and value of engagement rings.

Hamermesh found a premium for good looks and a penalty for bad looks in the workplace. A very handsome man is poised to make 13 percent more during his career than a “looks-challenged” peer. Above-average looking women earn 4% more than the average, while above-average looking men earn 3% more. Interestingly, Hamermesh found that below-average women earn 3% less, but below-average men are penalized more. Hamermesh says women have more latitude than men in choosing whether to work for pay, and that beauty affects that choice. At the time of his research (2008), women were more likely than men to stay out of the labor force. Unattractive women appear to be selected out of the labor market.

Melvin Konner, esteemed author and professor of anthropology and behavioral biology at Emory University, sums it up rather nicely with a final point about the downside of beauty bias: “Social psychologists have known for decades that the more attractive are more likely to be favored by teachers, to be successful at work, even be acquitted by a jury. The effect is clear to everyone who watches the news and wonders why people have to be good-looking to explain the budget crisis. The answer: more of us believe them. But bias toward beauty is bias against those who lack it.” (Why the Reckless Survive and Other Secrets of Human Nature)

18. Beauty and Political Orientation [index]

Beauty among women often translates to political conservatism, according to clinical psychologist Hector Garcia, author of Sex, Power, and Partisanship. Garcia cites one study in which researchers measured sex-typical features among congresswomen in the US House of Representatives. Researchers found that Republican congresswomen had far more feminine faces than their Democratic counterparts – what became known as the “Michele Bachman effect,” after the attractive former Republican representative from Minnesota. Researchers also discovered that the more feminine the congresswoman’s face, the more conservative her voting record.

In another study, subjects rated the attractiveness of both male and female politicians in Australia, the European Union, Finland and the United States. Across this wide breadth of political cultures, politicians on the Right were rated as significantly more attractive than those on the Left. This study also found that voters will infer that more beautiful candidates fall more to the Right. “We seem to know instinctively,” says Garcia, “that beauty means conservatism and may translate to social dominance.”

Another study found that men and women who rate themselves as more attractive tend to score higher on the social dominance orientation (SDO) scale. SDO reflects the extent to which an individual wishes his or her group to be dominant over another. SDO has been found to predict political conservatism and its corollaries, including economic conservatism and racial prejudice. Subjects primed to feel attractive were more likely to feel they had more power, social class, and greater status. They scored higher on the SDO scale.

We know women prefer men with higher social status and resources. The most beautiful women attract those men; they win big in the marriage sweepstakes. Attractiveness connotes good genes, which has bargaining power. So, it is no surprise these women will be inclined to support policies that benefit their (more conservative) husbands and their families. Longitudinal research has also found that after women get married (regardless of beauty and socioeconomic status), they tend to develop more socially conservative attitudes.

19. Phenomenology of Beauty — Mostly Questions [index]

What does it feel like to be beautiful? What does it feel like to be perceived as beautiful by “competing” members of the same sex (intra-sexual competition) and competing members of the opposite sex desiring your attention (inter-sexual selection)? What does it feel like to be perceived as beautiful by bosses, co-workers, subordinates, and the myriad personnel in the human service economy? By people on the street? What skills, interests, and talents are embellished by beauty and what traits of intelligence or character may be under-acknowledged, or even underdeveloped?

We know from research that beauty brings immense benefits of romantic and sexual access to preferred mates, perceived positive character traits, career opportunities, increased socio-economic status, and receipt of helping behavior and altruism. But we also know from happiness research that humans will “adapt hedonically” to any good fortune and pleasurable activity, thereby rendering the “phenomenology of benefits” to eventually plateau. Are beautiful people happier? Are the most beautiful the best judge of their privilege given our ubiquitous psychology to eventually take most things for granted? Are beautiful people actually willing to own their advantages, given the conclusions that may be drawn by others about their character and talent?

This author has described the phenomenology of the “people of the adored” vs. the phenomenology of the “people of the longing,” the latter being mostly heterosexual men in pursuit of beautiful women within a ruthless system of inter-sexual selection. The experience of these two “tribes” of people would appear to be 180 degrees different along dimensions of possibility and pleasure.

No doubt, beautiful women are more subject to the male gaze and inappropriate advances. They may believe, and experience, that being looked-over is indeed worse than being overlooked. Beautiful heterosexual women have to deal with mates who may be more jealous and engage in more mate guarding against the constant attempts of “poaching” by other males. That is not a good relationship dynamic.

What does it feel like to be sexually desired by so many people? Is that always a good thing? Being beautiful must have some downsides. What is the phenomenology of beauty? How does it feel to be born a genetic celebrity? The answers would help us all cope with some hard truths about the science of beauty, our hard-wired preferences, and our hedonic psychology.

20. Female Sex Appeal — What Men Want [index]

21. Male Sex Appeal — What Women Want [index]

22. Conclusion and Summary [index]

Human beings share universal, hard-wired preferences for physical traits that are pleasing to the eye — traits we find sexually attractive and aesthetically pleasing, or “beautiful.” Beauty is highly prized in prospective mates because it is a proxy for reproductive fitness and genetic strength. It is more than mere aesthetics. Beauty is nature’s shorthand for health and fertility, for reproductive capacity — visual cues that a woman or man has the potential to bestow good genes on future generations. Attraction and beauty are mostly inseparable from each other and from sexual selection generally. “Beauty may be in the eyes of the beholder, but those eyes, and the minds behind the eyes, have been shaped by millions of years of human evolution” (David Buss, The Evolution of Desire, p. 53).

23. Biography [index]

Baumeister, R., Tice, D. (2001). The Social Dimension of Sex.

Buss, D. (1994). The Evolution of Desire, Strategies of Human Mating.

Buss, D., Meston, C. (2009). Why Women Have Sex.

Cowley, G. (1996). The Biology of Beauty, Newsweek, June.

Etcoff, N. (1999). Survival of the Prettiest, The Science of Beauty.

Fisher, H. (1992). The Anatomy of Love.

Gangstad, S. Thornhill, R. (1994). Facial attractiveness, developmental stability, and fluctuating asymmetry. Ethnology and Sociobiology, 15(2) 73-85.

Garcia, H. (2019). Sex, Power and Partisanship.

Geher, G., Kaufman, S. (2013). Mating Intelligence Unleashed.

Gutierres, et al. (1999). Beauty, dominance, and the mating game: contrast effects reflect gender differences in mate selection. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25.

Hamermesh, D. (2011). Beauty Pays.

Johnson, V., Franklin, M. (1993). Is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Ethnology and Sociobiology, 14, 183-199.

Konner, M. (1990). Why the Reckless Survive and Other Secrets of Human Nature.

Langlois, J. et al. (1990). Infant differential social responses to attractive and unattractive faces. Developmental Psychology, 26, 153-159.

Langlois, J. (1990). Attractive faces are only average. Psychological Science, 1, 115-121.

Levine, M. (2001). Why I Hate Beauty, Psychology Today, July-August.

McAndrew, F. (2017). Beauty Cues, Psychology Today, November-December.

Miller, G. (2000). The Mating Mind.

Paris, W. (2017). Laws of Attraction. Psychology Today, July-August.

Prum, R. (2017). The Evolution of Beauty.

Ryan, M. (2018). A Taste for the Beautiful, The Evolution of Attraction.

Thornhill, R. & Gangstad, S. (2008). The evolutionary biology of human female sexuality.

Waldman, A. (2013). The Problem of Female Beauty,” The New Yorker, October.

Wright, R. (1994). The Moral Animal.