Chris Rock’s Selective Outrage: The Truth of Sexual Selection and Preference for Younger Women

Don’t hate the player; hate the game. ~ Chris Rock

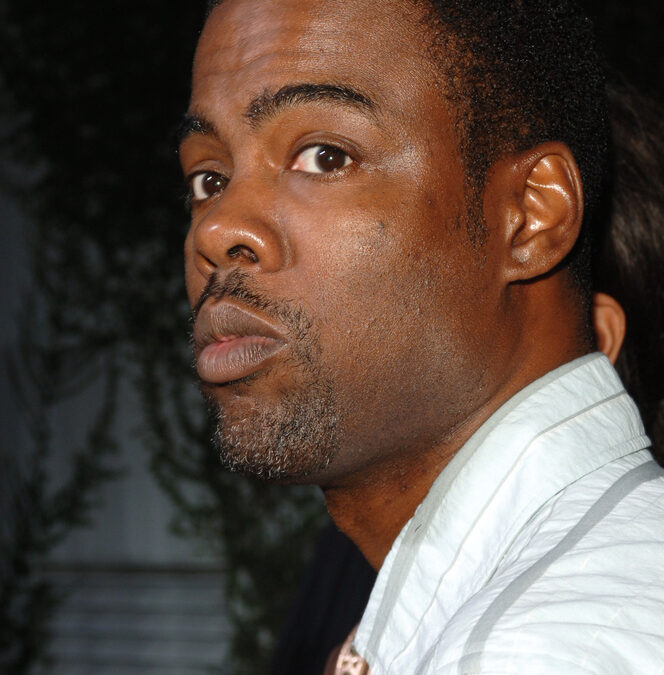

Chris Rock was sharply criticized for some of his comedic riffs in his Netflix special Selective Outrage. Speaking to a predominantly Black audience in Baltimore, he delivered incisive observations about the American obsession with attention and being a victim. He joked about the many abortions he paid for and cathartically unleashed his feelings about the infamous slap by Will Smith and the “entanglements” of Smith’s wife, Jada Pinket Smith.

Rock also told the truth about sexual selection, illustrating three points (Chris Rock in red):

1. There is a collusion between men and women about sex and money – the “erotic-economic bargain.”

I have made millions of dollars. And every dime I have made, I have spent on pu..y or pu..y adjacent.

Younger women just want you to buy them shoes, but the 45–50-year-old woman wants a new roof.

I’ve paid more college loans off than Joe Biden!

I want to live in a place where women are voluntarily not working and wear yoga pants in the middle of the afternoon.

You can lose a lot of money chasing women, but you will never lose women by chasing money. (From I Think I Love My Wife.)

2. Female beauty has immense power and privilege.

Nothing more powerful than female beauty. Nothing.

A beautiful woman can stop traffic. There is nothing about a man that can stop traffic.

Beyonce is so fine, that if she worked at Burger King, she could still marry Jay Z. Now if Jay Z worked in a Burger King….

3. Sexual attraction for younger (fertile) women versus older women is a male evolutionary adaptation thousands of years in the making.

I didn’t get rich and stay in shape to talk to Anita Baker. I am trying to f…k Doja Cat.

I am interested in women my age — that is 10-15 years younger.

Important note:

Before I go any further with the studies about age preference, let me assure you (if assurance will make this fact of life more palatable) the average man does not usually pursue the younger women he desires. He is more “interested,” as a practical matter, in women closer to his age. The average man has no relationship with a much younger woman unless it is a paid sex worker, of which there are several versions. (I will address “sex work” in my next post, also related to age.) But what rich and famous men do in practice is another story. More on that below.

Criticism From the Left Prompted This Post

Let me also remind my readers: I am progressive in my worldview of politics, female equality, and social justice. But, I push back against the critique from the Left that denies biological differences between the sexes and vilifies male sexuality in broad terms. It is the criticism of Rock from the liberal media that prompted me to do this post and trot out research evidence — at the risk of beating a dead horse. Otherwise, I would have (perhaps more wisely) left the “Chris Rock thing” alone.

In this post: preference for younger women and age discrepancies:

• Data from OkCupid and Zoosk

• Research from Finland and other cultures

• “Most desired” is not the same as “most interested in”

• Ages of famous movie couples

• “Chris Rock Effect”

• Age differences of 68 celebrity partnerships

Liberal Media Not Happy with Rock

Predictably, there was considerable “selective outrage” of a different kind against Rock from the liberal media. About his attraction to younger women, NPR media critic Eric Deggans called Rock “sexist.” The woman interviewing Deggans on NPR said Rock would be lucky to have Anita Baker. Anita Baker is 65. Chris Rock is 58. Doja Cat is 27, 31 years younger than Rock. See below the age differences between male celebrities and their partners.

Sexual Attraction to Younger Women – Let’s Look at the Data

Most Desirable Age for Men and Women from OKCupid

Christian Rudder, co-founder of OKCupid (and Harvard math major) collected data from millions of users on the website to reveal the ages men and women found “most desirable” in the opposite sex. The data was analyzed for men and women in their 20s up to the age of 50. Rudder displayed the resulting (now infamous) graphs in his book, Dataclysm: Who We Are When We Think No One’s Looking.

Here is what the data revealed:

Heterosexual Men Most Desire a Woman in Her Early 20s

Rudder reported that men in their twenties clicked on pictures of women about two years younger. But men in their 50s clicked on women 25 years younger than themselves.

“No matter how old a man gets, he will be attracted to a woman in her early twenties,” Rudder asserts. Twenty-year-old and forty-nine-year-old heterosexual men cite women aged 20-24 (average age was 20.77) as the most desirable.

Women Are Different

Women preferred someone roughly their own age. Before 30, they’re looking for slightly older men. Throughout her forties, a woman is most attracted to men at around the age of 40. A 50-year-old woman will most like the looks of a 46-year-old man. Forty-year-old men will likely provide “true signals” of achieved status, position, financial resources, and career trajectory.

“If we want to pick the point where a man’s sexual appeal has reached its limit, it’s there: 40,” Rudder explains.

Zoosk Dating App Data

According to data from the dating site and app, Zoosk, which claims 40 million members, 60% of men are attracted to women younger than them, and nearly 56% of women prefer older men.

The Design of Human Reproduction

Data from dating websites is just one piece of a mountain of scientific evidence backing the theory that men almost always prefer younger women for short-term and long-term mating. This preference comports directly to the psychological and physiological design of human reproduction.

Finnish Study Aligns with OkCupid

Results from research conducted (2014) in Finland were directly aligned with OKCupid’s findings and other prior research. Reporting in Evolution and Human Behavior, the study found that men of all ages fantasize about one type of woman: the 20-something female.

Researchers surveyed 12,656 men and women aged 18 to 49 to study age preferences in sexual partners. They asked each participant which age group they were most sexually attracted to during the last 12 months and which age group they engaged in sexual activity with.

Age Preferred by Finish Men and Women

Just as the researchers hypothesized, the results varied by gender. Women tended to be interested in men who were similar in age or slightly older. Specifically, women in their late teens and twenties preferred male partners about four years older, and the age gap preference lessened as women got older.

Again, men tended to be interested in one single age group: women in their mid-twenties, and this held true even in younger men in their late teens or early twenties.

Roots in Evolutionary Biology

Finnish researchers argued (as do hundreds of scientists) that both male and female age preferences have roots in evolutionary biology. They hypothesize that women go for older men due to the “resources” they can offer, including the ability to help with offspring: “Men mature later than women, and in our evolutionary past, raising human offspring to nutritional independence necessitated bi-parental care.”

Men Are Interested in Fertile Women

The researchers also asserted that men’s sexual preference is shaped with offspring in mind; specifically, they are interested (even unconsciously) in women who are fertile.

“The highest fertility has been estimated to occur in the mid-twenties, with a decline after the age of 35,” the researchers explain. “Especially for short-term mating, men show a high interest in fertile women, that is, women in their twenties.”

Sexual Preference for Younger Women is World-wide

Across cultures, men marry women around their own age when they are young, but much younger women if they remarry later in life (Kenrick, 2010; Kenrick & Keefe, 1992). For example, evolutionary psychologist Douglas Kenrick studied the ages of spouses on the Pacific Island of Poro in the Philippines. Young men on Poro married women around their own age. But older men married women almost two decades younger than them (Kenrick & Keefe, 1992).

Marriage Data Across History and Geography

As reported on background by Kenrick, marriage data reflect these preferences in a diverse array of historical and geographical conditions, including North Americans, Brazilians, Moroccans, the Herrero in Africa, and inhabitants of prosperous 17th-century Amsterdam.

Men and Women Seek Different Resources

Like the Finnish researchers, Kenrick suggested that age differences in mating preferences seem to be linked to the fact that women and men seek relatively different resources in their mates. Quoting Kenrick:

“Women around the world and throughout history have placed relatively more emphasis on a man’s social status and ability to provide resources (which tend to increase as the man gets older). Conversely, men tend to seek features associated with fertility, such as a healthy appearance and relative youth (a woman’s fertility is high in her twenties, but declines as she ages).”

More Evidence from the Netherlands

Evolution and Human Behavior (2001): “Age preferences for mates as related to gender, own age, and involvement level.” (Kenrick, et al.)

Kenrick and colleagues also examined the minimum and maximum ages for mates in the Netherlands across five different levels of relationship involvement (marriage, serious relationship, falling in love, casual sex, and sexual fantasies), comparing individuals who were 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 years old. Consistent with previous findings, women preferred partners of their own age, regardless of the level of relationship involvement. Men, on the other hand, irrespective of their own age, desired mates for short-term mating and for sexual fantasies who were in their reproductive years. However, regarding long-term mates, men preferred mates who, although younger than them, were sometimes above the age of maximum fertility.

Desires Unconstrained in Sexual Fantasies

What would adults ask for if their desires were unconstrained by the marketplace? One way to address this question is to consider sexual fantasies. Sexual fantasies, which do not involve pragmatic constraints, demonstrate the most robust evidence of male sexual attraction towards women in the years of peak fertility, according to Kenrick.

Most Desirable is Not the Same as “Most Interested In.”

The OKCupid study found that men are “most interested in” women closer to their own age. There is an essential distinction between what men desire and how they act. Being “interested” in a woman means someone that a man might pursue with a realistic chance of reciprocity.

Despite older men finding much younger women extremely attractive, men on OKCupid were highly unlikely to message any of these women. Men most often messaged women closer to their own age.

“Matched” with Women 1-3 years Younger on Zoosk

According to Zoosk researchers, “though men are often attracted to women up to 10 years younger than them, the women they match with (the women who like them back) tend to be only 1-3 years younger.” Indeed, according to the 2014 Current Population Survey, the average age difference for heterosexual couples was a man 2.3 years older than a woman.

Assortative Mating – Age and Other Similarities

Research in mate selection by evolutionary psychologists and sociologists confirms that men and women tend to “sort” along the lines of age, background, proximity, education, and relative mate value – a value determined primarily by physical attractiveness for women and wealth and status for men. Physical attractiveness and stature (being “tall, dark, and handsome”) are assets for men but are secondary to their status and resources for female preference in a long-term mate.

A Younger Woman is Mostly “Out of Your League”

Men desire younger women, but the average man knows he can only realistically pursue a much younger woman if he brings great assets to the table. The mating market tends to match people at the level of their “mate value” with such precision that most men and women know not to go completely “out of their league.” Since men do 95% of pursuing, this calculation is made primarily by men. For the average guy, the women he is “interested” in are preset or dictated by the parameters of the sorting process in his mating pool. Most men have received many direct refusals and turndowns. Avoiding more rejections also shapes his perceptions of who he “should” be interested in.

Older Hollywood Actors and Celebrities Paired with Young Women

Phantom Thread was nominated for the 2018 Academy Award for best picture. Daniel Day Lewis’s character is a highly successful dressmaker — wealthy and well-connected to London’s social elite. He has a passionate relationship with a young, beautiful waitress, played by Vickie Krieps.

Daniel Day Lewis is 26 years older than Vicki Krieps. This kind of age spread is not unusual in Hollywood. In the classic romantic movie Casablanca, which won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1942, Humphrey Bogart was 43, and Ingrid Bergman was 24.

In Gone with the Wind, Clark Gable was 37, and his romantic interest, Vivien Leigh, was 25. People magazine’s cover once asked, “Why are leading actors matched with costars half their age?” The magazine article suggested the possibility that it was because Hollywood directors tend to be older males, who are “trying to relive their youth.”

A look at the research findings on actual mating preferences suggests that normal human preferences drive the Hollywood director’s choices rather than the other way around.

The Chris Rock Effect – In a League of Their Own

Men of great wealth, talent, fame/status, and a modicum of charm, can pursue their preferences for younger women much more readily than the average man. There is no evidence that Chris Rock is actually pursuing Doja Cat, but he has the assets to date a woman who is 31 years younger.

Erotic and Economic Power – the Age of Celebrity

Rich men and beautiful women find each other at the high end of male and female mate value. The erotic-economic bargain is commonly demonstrated by the preference and ability of older men to partner with significantly younger women – women usually in their fertile years at the time of the union. Please take a look at the list below of high-status, celebrity, rich men and their partners. You will see up to 60+ years of an age difference. Money can allow men to “mate down” decades to find beautiful women who will choose to partner with them.

Of course, many of these celebrities have attractive intellectual, physical, and emotional qualities (i.e., their talent), but what they have most importantly is high status and great wealth.

Male Celebrities with Younger Women

Male celebrities with younger women demonstrate evidence of the following:

• the power of fame and money to attract younger women – with relative doses of charm, talent, and physical attractiveness;

• how resources, prestige, and status drive the mating system and female choice;

• how men, given options literally “afforded” them, will naturally pursue the most beautiful women;

• how the resistance against age difference and proclamations of “he is too old” are relative to the degree of fame and money the man possesses.

Age Differences Between Male Celebrities and their Partners

All the men listed below are rich and famous. All the women are beautiful. This is the “economic-erotic bargain” in stark terms.

• Jay Marshall and Anna Nicole Smith, 62 years

• Hugh Hefner and Crystal Harris, 60 years

• Dick Van Dyke and Arlene Silver, 46 years

• Mick Jagger and Melanie Hamrick, 43 years

• Robert Duval and Luciana Pedraza, 41 years

• Tony Bennet and Susan Crowe, 40 years

• Patrick Stewart and Sunny Ozell, 38 years

• Rupert Murdoch and Wendy Deng, 38 years

• Charlie Chaplin and Oona O’Neill, 36 years

• Clint Eastwood and Dina Ruiz, 35 years

• Woody Allen and Soon-Yi Previn, 35 years

• David Foster and Katharine McPhee, 34 years

• Doug Hutchinson and Courtney Stodden, 34 years

• Lee Majors and Faith Noelle Cross, 34 years

• Gary Grant and Dyan Cannon, 33 years

• Dennis Quaid and Santa Auzina, 33 years

• Aristotle Onassis and Jackie Kennedy, 33 years

• Billy Joel and Alexis Roderick, 33 years

• Bing Crosby and Kathryn Grant, 33 years

• David Lynch and Emily Stofle, 32 years

• Billy Joel and Katie Lee, 32 years

• John Cleese and Jennifer Wade, 31 years

• Ronnie Wood and Sally Humphreys, 31 years

• Nicolas Cage and Riko Shibata, 31 years

• Jeff Goldblum and Emilie Livingston, 30 years

• Frank Sinatra and Mia Farrow, 30 years

• William Shatner and Elizabeth Anderson, 30 years

• Alan Thicke and Tanya Callau, 28 years

• Rod Stewart and Penny Lancaster, 27 years

• Eric Clapton and Melia McEnery, 27 years

• Nelson Mandela and Graca Machel, 27 years

• Larry King and Shawn Southwick, 26 years

• Alec Baldwin and Hilaria Thomas, 26 years

• Bill Murray and Jenny Lewis, 26 years

• Steve Martin and Anne Stringfield, 26 years

• Rupert Murdoch and Jerry Hall, 26 years

• Dane Cook and Kelsi Taylor, 26 years

• Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, 25 years

• Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones, 25 years

• Rod Stewart and Rachel Hunter, 25 years

• Kelsey Grammer and Kayte Walsh, 25 years

• Bruce Willis and Emma Heming, 24 years

• Rene Angelil and Celine Dion, 24 years

• Donald Trump and Melania, 24 years

• Christopher Knight and Adrianne Curry, 23 years

• Johnny Depp and Amber Heard, 22 years

• Harrison Ford and Calista Flockhart, 22 years

• Sylvester Stallone and Jennifer Flavin, 22 years

• Kevin Costner and Christine Baumgartner, 22 years

• Carlo Ponti and Sophia Loren, 22 years

• Glen Campbell and Kim Campbell, 21 years

• Floyd Mayweather and Raemarni Ball, 20 years

• Prince Albert of Monaco and Princess Charlene, 20 years

• Warren Beatty and Annette Bening, 19 years

• Jason Statham and Rosie Huntington-W., 19 years

• Anthony Hopkins and Stella Arroyave, 19 years

• Eddie Murphy and Paige Butcher, 19 years

• Dominic Purcell and AnnaLynne McCord, 18 years

• Christian Slater and Brittany Lopez, 18 years

• Howard Stern and Beth Ostrosky, 18 years

• Paul McCartney and Nancy Shevell, 18 years

• Jerry Seinfeld and Jessica Sklar, 17 years

• Oliver Sarkozy and Mary-Kate Olsen, 17 years

• George Clooney and Amal Alamuddin, 17 years

• Bradley Cooper and Suki Waterhouse, 17 years

• Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes, 16 years

• Kevin Kline and Phoebe Cates, 16 years

Related Posts

Dynamics in the Mating Economy: Domain #1 of Male-Female Difference

• erotic-economic bargain – the ultimate exchange in the mating economy

Mate Value of High-Income Men: Seeking Arrangements and the Erotic-Economic Bargain

• research by Rosemary Hopcroft: Evolution and Behavior (September 2021)

• research by Catherine Hakim (Univ. of North Carolina) on “erotic capital”

Please Note: Your comment may take up to 12 seconds to register and the confirmation message will appear above the “Submit a Comment” text.